The Algonquin Round Table in caricature by Al Hirschfeld. Seated at the table, clockwise from left: Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Marc Connelly, Franklin P. Adams, Edna Ferber, George S. Kaufman, Robert Sherwood. In back from left to right: frequent Algonquin guests Lynn Fontanne and Alfred Lunt, Vanity Fair editor Frank Crowninshield and Frank Case.

The first thing I do in the morning is brush my teeth and sharpen my tongue.

I've recently been reading The Feminine Mystique. Betty Friedan begins her argument about what the hell happened to American women and their needs and desires in the 50s and 60s with this theory: before the Second World War women in this country, especially after they got the vote, were freer and more able and willing to be career women, to be what their mothers before them could not. They had to step up to the bread-winning plate during and after the First World War, when so many men were absent or lost. It was the men returning from the Second World War dreaming of a cozy hearth and home in the 40s and 50s who used women's magazines as the medium to get the women back into the kitchens. I'm not sure yet if I completely accept her hypothesis, as I'm still mid-read, but watching Leigh as Parker navigate her way through a "man's world" in 1920s New York City did at times echo this view.

Tell him I was too fucking busy—or vice versa.

Portrait of Art Samuels, Charlie MacArthur, Harpo Marx, Dorothy Parker and Alexander Woollcott, ca. 1919.

Dorothy Parker wrote poems from an early age, submitted them to magazines to be published, and managed to get a job with Conde Nast. She was first steered towards the more "female" publication, Vogue. She eventually became the theater critic at another Conde Nast publication, Vanity Fair, taking the post once held by P.G. Wodehouse, where she honed her trademark wit. And did she ever hone it, sharp as a knife. One of her most famous barbs was a review of Katherine Hepburn's performance in a now-forgotten play, The Lake in 1934:

She runs the gamut of emotions from A to B.

Parker's sometimes caustic reviews eventually got her fired from Vanity Fair, which didn't want to offend powerful Broadway producers. Her opinions may have temporarily been stifled, but she had formed some fiercely loyal friends in co-workers Robert Benchley and Robert Sherwood, who also resigned in protest and solidarity with Parker. Jobless, they still continued their daily luncheon ritual at The Algonquin, which attracted more and more of their friends and literary contemporaries. This not-so-motley crew were instrumental in the forming of The New Yorker, and became known as the Algonquin Round Table. The movie is like a who's who of the smartest smart-alecks of the early twentieth century, played by an amalgam of the sons and daughters of Hollywood actors, and New York character actors: Campbell Scott, Matthew Broderick, Andrew McCarthy, Wallace Shawn, Sam Robards, Lili Taylor, Gwyneth Paltrow, Nick Cassavetes, Stanley Tucci.

Imagine becoming famous for being smart. Who can we say that of today's crop of fashionable celebrities? So many phrases that are in the popular lexicon can be traced to the witty Parker, who always managed to blend her wit with a dose of misery.

Men seldom make passes at girls who wear glasses.

Parker and her friends were a tight group. They lived, loved and drank—a lot—together. They were at the height of their powers and their youth during Prohibition, and the movie shows how much a role bathtub gin, speakeasies, and other substances were a part of their lives.

I like to have a martini,

Two at the very most.

After three I'm under the table,

after four I'm under my host.

Parker fell in love with Charles McArthur, who took their love affair far less seriously than she did. It resulted in an abortion and a broken heart. Matthew Broderick is actually quite sexy in the role, and believably seduces the only slightly resistant Parker, who may or may not also have had unresolved feelings for her long-term pal Benchley, nicely played by Campbell Scott. Broderick manages to remain sympathetic while simultaneously being, as Parker might characterize him, an utter shit.

It serves me right for putting all my eggs in one bastard.

Like another biopic I watched recently set in the same era, Coco Before Chanel, the relationships and intertwining lives of these people were beyond complicated. Have we become steadily more and more conservative since the 20s?

Heterosexuality is not normal, it's just common.

It is clear that Parker was most definitely damaged by the busted affair with McArthur, as she tried to take her own life, but it is also apparent that she consciously delved into her pain for her art. She was a very self-aware woman.

Razors pain you;

Rivers are damp;

Acids stain you;

And drugs cause cramp.

Guns aren’t lawful;

Nooses give;

Gas smells awful;

You might as well live.

Parker and her vicious circle did everything together. They took vacations together, worked together. In the 30s Parker went out to Hollywood, as did Sherwood and Benchley. A typical New Yorker, Parker disdained Hollywood and its environs, but not the cash that accompanied her screenwriting projects. She contributed to some very successful movies, including the 1937 A Star is Born, Saboteur and The Little Foxes.

If you want to know what God thinks of money, just look at the people he gave it to.

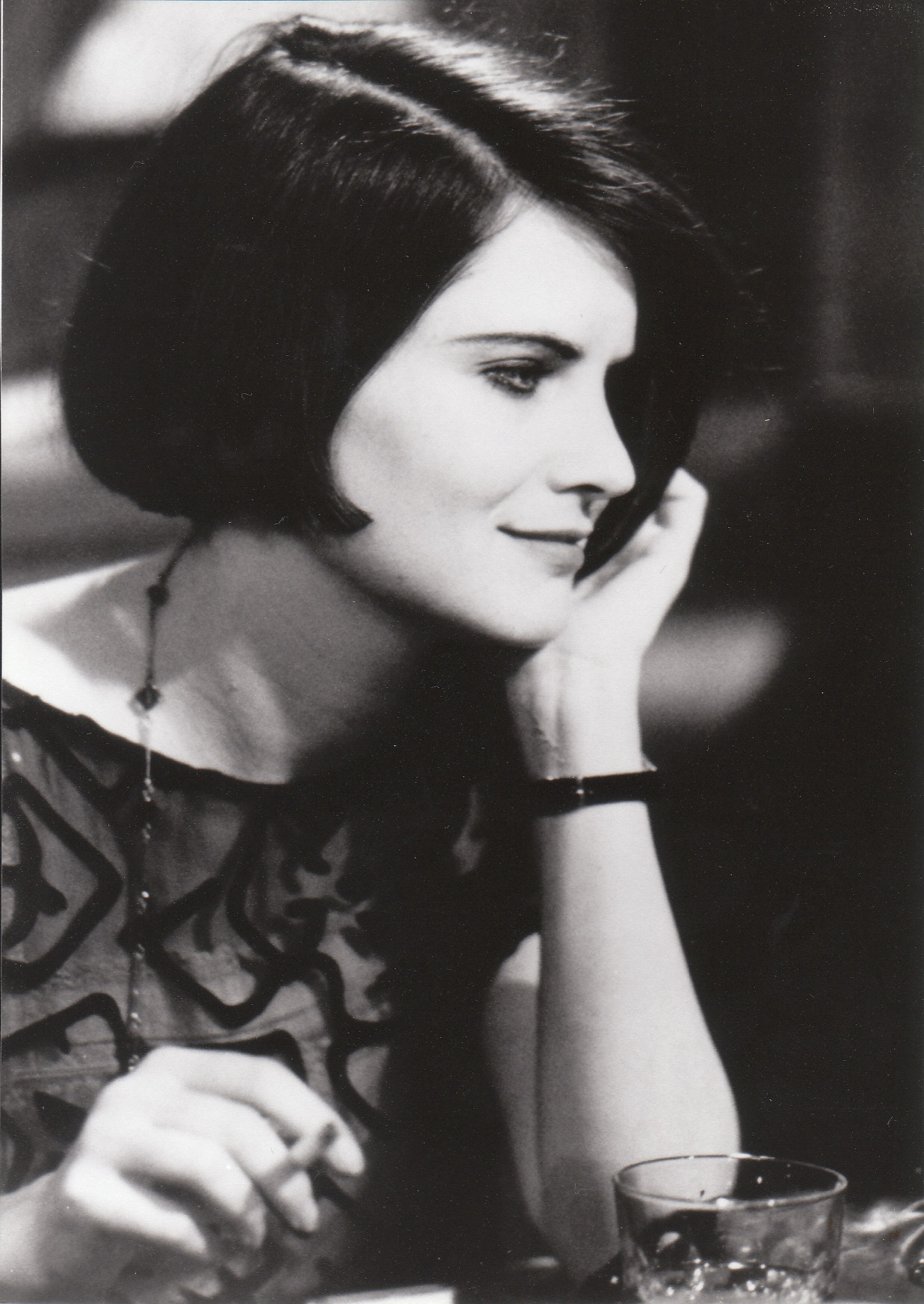

Jennifer Jason Leigh gives an uncanny and poignant interpretation as Parker.

Parker was very vocal about human rights, and was placed on the Hollywood blacklist, which led to her return to New York in the 1950s. Leigh recites bits of Parker's poetry throughout the film, in a progressively alcoholic slur. Her vocals sound at first affected, but after hearing Parker's own recitations of her poetry it is clear that the actress did her homework.If I didn't care for fun and such,

I'd probably amount to much.

But I shall stay the way I am,

Because I do not give a damn.

There is a nice little documentary attached to the DVD, which helps underscore as well as showcase how accurate a portrayal it is of Parker's life. The one question it didn't answer, apart from acknowledging her political sympathies, was why Parker left her estate to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Foundation at her death in 1967. The estate went to the NAACP after his death the following year. Unfortunately, Parker's friends were not so steadfast at the end. Lillian Hellman, who was the executrix of her will, contested her final wishes, and Parker's ashes were shuttled from one place to another until the NAACP was finally able to inter them in Baltimore in 1988.

Time doth flit; oh shit.

Dorothy Parker was smart, verbally athletic—a sassy broad. She was the opposite of politically correct. If attitudes cycle round again, I hope that we are in for a nouveau 20s, without all the alcoholism. Blogs and the internet give many the opportunity to speak their mind. Unfortunately, most don't understand that snark doesn't equal wit. Through blogs and other writing there is a real chance to get one's voice and opinion heard. More and more women could stand to speak their minds, creatively, a la Dorothy Parker.

Quotes from Goodreads

1 comments:

Dorothy Parker was the cat's meow and the cat's claws, all in one. Jennifer Jason Leigh was good, but who would you pick if an Algonquin Round Table movie was made today?

Take a look at

Algonquin Round Table Mysteries

Currently Christina Ricci is in the lead as a potential Dorothy Parker.

Post a Comment